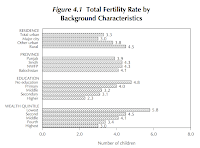

The total fertility rate among women of childbearing age in rural Pakistan is very high at 5.6 births per women. When addressing this high fertility rate, it is important to determine causation. In rural Pakistan, high fertility can be attributed to a variety of compounding determinants that relate to biological, social, environmental, economic, and political factors.

Fertility in rural Pakistan is primarily effected by socioeconomic determinants. Rural regions have a higher percentage of poverty compared to urban areas; 56% are in the lowest or second lowest wealth quintile (Pakistan). Poverty has a positive association with fertility; as levels of poverty increase, so does the TFR. Furthermore, women of the poorest fifth use contraception at a lower rate than women of the wealthiest fifth. Since the majority of women living in rural areas are poor, a high TFR would be expected.

Women in rural Pakistan are also less likely to be educated, another key social determinant of fertility. If a girl enrolls in secondary school and completes her education, she is likely to delay marriage and consequentially delay childbearing; if childbearing is delayed, a women will have less children. However, only 3.9% of girls in rural Pakistan receive secondary education and 68% receive no education (Pakistan). “Adolescent motherhood is widespread in rural areas among girls with little or no schooling, and among those with low socioeconomic status,” (Sultana). Of those girls who attended 5-9 years of school, only 33% where married before 20 and of those girls who received no education, 68% where married (Sultana). Marriage in Pakistan is usually immediately followed by pregnancy and, as a result, the average age at first childbirth is very young: 21 years.

Women in rural Pakistan are also less likely to be educated, another key social determinant of fertility. If a girl enrolls in secondary school and completes her education, she is likely to delay marriage and consequentially delay childbearing; if childbearing is delayed, a women will have less children. However, only 3.9% of girls in rural Pakistan receive secondary education and 68% receive no education (Pakistan). “Adolescent motherhood is widespread in rural areas among girls with little or no schooling, and among those with low socioeconomic status,” (Sultana). Of those girls who attended 5-9 years of school, only 33% where married before 20 and of those girls who received no education, 68% where married (Sultana). Marriage in Pakistan is usually immediately followed by pregnancy and, as a result, the average age at first childbirth is very young: 21 years. The cultural norms in conservative areas of rural pakistan make it acceptable and, in many cases, expected for a woman to bear many children. There is also a difference between the number of children a women wants compared to the desire of her husband. When compared, the desired number of children slightly higher among men; women desire 3.9 children whereas men desire 4.0 (Sultana). Furthermore, rural communities are primarily Islamic, which effects their attitude toward contraception and family size. Contraception is not forbidden in Islam; only permanent methods, such as sterilization, are taboo. Even still, conservative rural communities tend to also be wary of contraception; they see it as potentially promoting promiscuous sexual behavior. However, cultural norms may not play as big a role as expected: “Due to modernization, the impact of culture and religion is fast disappearing from determining the demographic transitions taking place. It is clearly social and economic [factors that matter] and of course, at the top of it all, what public policies each country follows,” (Zuehlke).

Apart from cultural, social, and economic factors, another determinant of fertility for women in rural Pakistan is access. There is almost no availability family planning and pre and post natal care due to their isolated location. Lack of access to family planning means that modern contraception is used at a very low rate, only 17.7%, and there is a high unmet need at 31%. Contraception is “the most important intermediate fertility variable determining fertility levels,” (Davis). There is a negative association between contraceptive use and fertility; as contraceptive use increases, fertility decreases. Fertility also depends on the type of contraceptive that is used, as some methods are more effective than others.

Lack of access to family planning services in rural Pakistan is primarily due to lack of effective government interventions. The Pakistani government has so far not implemented a successful family planning program (Karim). Any programs that have been implemented by the Pakistani government cannot be reached by the women in rural areas. “In Pakistan, because there has not been an effective family planning program, only women who are living in urban areas, more educated, or coming from upper- or middle-class families are using contraceptives...” (Zuehlke).

Overall, high fertility rates in rural Pakistan can primarily be understood through examining their social, economic, and political environment. Living in rural areas of Pakistan puts women at an inherent disadvantage when it comes to family planning; they are subject to more of the compounding key determinants that cause high fertility such as poverty, lack of education, and barriers to access.

Overall, high fertility rates in rural Pakistan can primarily be understood through examining their social, economic, and political environment. Living in rural areas of Pakistan puts women at an inherent disadvantage when it comes to family planning; they are subject to more of the compounding key determinants that cause high fertility such as poverty, lack of education, and barriers to access.p.s.- Dr. Crupain, here is my new problem definition: High fertility rates among women of childbearing age in rural Pakistan from 1970-2010.

Do you think this sounds better?

Also, are we able to include charts in our paper for clarification?

Works Cited:

"BBC - Religions - Islam: Contraception." BBC - Homepage. 07 Sept. 2009. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/islamethics/contraception.shtml>.

Davis and Blake 1956. “Social Structures and Fertility: An Analytic Framework” Econ. Dev and Cultural Change 4:211-235

"Population Dynamics - Countries of WOA!! Population Awareness." World Overpopulation Awareness. 27 Nov. 2010. <http://www.overpopulation.org/culture.html>.

“Population & Economic Development Linkages 2007 Data Sheet.” Population Reference Bureau. 2006.

"Pakistan: DHS, 2006-07 - Final Report." Demographic and Health Surveys, 2006-2007.

Sandra, Yin. "Pakistan Still Falls Short of Millennium Development Goals for Infant and Maternal Health - Population Reference Bureau." Home - Population Reference Bureau. Dec. 2007. <http://www.prb.org/Articles/2007/pakistan.aspx>.

Sathar, Zeba, Christine Callum, and Shireen Jejeebhoy. "Gender, Region, Religion and Reproductive Behaviour in India and Pakistan." IUSSP. Rockefeller Foundation, 2001. <iussp.org>.

Sultana, Munawar. "A Brief on Reproductive Health of Adolescents and Youth in Pakistan - Culture of Silence." The Population Council, Inc., 2005.

“World Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision.” United Nations. 2005.

Zuehlke, Eric. "Changes in Fertility Rates Among Muslims in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh - Population Reference Bureau." Home - Population Reference Bureau. Apr. 2009. <http://www.prb.org/Articles/2009/karimpolicyseminar.aspx>.